LBCF: Antiheroes

Jan. 16th, 2026 12:00 pmYeah damn right, she’ll rise again

Jan. 15th, 2026 09:07 pmCross my heart and cross my fingers

Jan. 14th, 2026 09:56 pmThe Academy Is…: 2005

Jan. 14th, 2026 04:35 pmThe Academy Is…, one of my favorite bands from this century (and yes, I feel old just typing that out), has recorded their first new album in eighteen years, titled Almost There, and will be putting it out in March. In the meantime, here is the first single from the album, “2005,” which is a paean both to that year and still being around more than 20 years later. Speaking as someone whose debut novel came out in 2005: Feel it.

Also if you want to preorder the album and merch, they have a shop.

— JS

The lumpers, the splitters, and me

Jan. 13th, 2026 08:58 pmA Minor Planet, a Major Thrill

Jan. 12th, 2026 10:16 pm

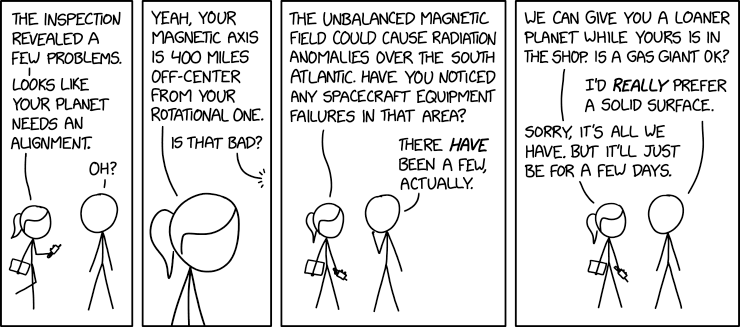

Our solar system has eight major planets, nine if you believe that Pluto Was Wronged. It also has literally thousands of minor planets, which are also colloquially known as asteroids, many of which reside in the “asteroid belt” between Jupiter and Mars. I learned some time ago that the International Astronomical Union, through its Working Group on Small Bodies Nomenclature, will give some of these minor planets, usually designated by number, an actual name. What kinds of names? Sometimes of geographical locations, sometimes of observatories, sometimes of fictional characters like Spock or Sherlock Holmes, sometimes of scientists (or their family members), and sometimes, just sometimes, they’re named after science fiction authors.

Like minor planet 52692 (1998 FO8), henceforth to be known as “Johnscalzi”:

This little space potato is a Main Belt Asteroid whose orbit is comfortably between Jupiter and Mars, has a diameter of about 10.7 kilometers, and has a “year” of about 5 years, 8 months and 10 days. If I start the clock on a ScalziYear today, it’ll be New ScalziYear’s Day on September 22, 2031. Plan ahead! If you want to look for Johnscalzi, the link above will tell you where it is, more or less, on any given day, but at 10km across and an absolute magnitude of 12.19 (i.e., really really really dim), don’t expect to find it in your binoculars or home telescope. Just know that it there, cruising along in space, doing its little space potato-y thing.

How do I feel about this? My dudes, dudettes and dudeites, I am so unbelievably stoked about this I can’t even tell you. It’s not an exaggeration to say this was something of a life goal, but not a goal that was in my control in any significant way. I suppose it might be possible to buy one’s way into having an asteroid named for you, but I don’t know how to do that, and I wouldn’t even if I did. How much cooler to be tapped on the shoulder by the International Astronomical Union, and to be told, here is a space potato with your name. I can die happier now than I could have a day ago. To be clear, I don’t plan to die anytime soon. But when I do, if they’re shooting remains into space that point, now they will have a place to aim me at.

Also cool: The name of the asteroid that’s in the catalogue next to mine. We geeked out about it on the phone just now. We’re Space Potato Pals!

Anyway, this is how my day is going. It’s pretty great. Highlight of the year so far, for sure.

— JS

Smart people saying smart things (01.11.2026)

Jan. 11th, 2026 08:52 pmThe Offline Archive

Jan. 11th, 2026 06:38 pm

In the current iteration of Whatever, the archive here goes back to March 2002, which is a time before all but one of my books (The Rough Guide to Money Online, now out of print and deeply outdated). That is nearly 24 years of writing here on a nearly daily basis, and millions of words, to go along with the millions of words that are in my other books and novels, all but three of which are still in print (the other two out of print books: The Rough Guide to the Universe and The Rough Guide to Sci-Fi Movies, both also out of date). Between this site and the books, there will be no lack of verbiage for people who are interested in me to go by; I will not die a mystery to history.

Nevertheless, there is a substantial part of my writing life which is no longer as easily accessible. Going from most recent to most distant, there are first the out of print books, the rights to which I own and which I might even put online at some point, but haven’t because doing so is a pain in the ass. I’d have to work from either old PDFs or scan everything in, and the effort required versus the value of the text is not there for me. You might find some of these on pirate sites, and inasmuch as I’m not doing anything with them at the moment, you’re welcome to them if you find them there (that said, don’t link to any of them in the comments, please).

Prior to that is the text of Whatever from between September 13, 1998 and March 26, 2002. This was an era where the Whatever was made from hand-rolled HTML rather than typed into dedicated blogging software (first Movable Type, then WordPress). Being hand-rolled meant that it was not easy to just transfer the text over; I would have had to cut and paste a couple thousand entries. Prior to the advent of Whatever there was an even earlier version of the site going back to March of 1998, which is when I secured the Scalzi.com domain and put up a static site, with columns and movie reviews from my newspaper days, new essays I wrote for the site, a couple of book proposals, and some extremely Web 1.0 site design.

None of this material is on the site proper anymore, but it’s still around after a fashion. One, I have a digital archive of it, duplicated in several places to ward off accidental deletion, and also it’s on the Internet Archive site (along with more recent iterations of this site), because I am not adverse to having the site archived in this way, and also because I personally find it convenient — if there’s something from this era I want to look at, it’s easier for me to look for it via the Internet Archive than my own archives. Among other things, the Internet Archive has maintained the architecture of the old site as well as the content of it. The Internet Archive is robust and useful but only gives the illusion of permanence; it could go away at any point. This is why I also have my own digital archive.

(The Internet Archive is also currently the only easy way to find anything I ever wrote on the former Twitter, as I permanently deleted my presence there, including all my tweets. I did, of course, download my own archive of tweets and have multiply saved it.)

Prior to this is my professional work up until I started being a full-time novelist: Work I did for AOL and other web sites, including columns at AMC, MediaOne and my own videogame review site, GameDad, and before then the columns, features and movie reviews I did for the Fresno Bee between September 1991 and March 1996. Again, I have my own digital archives of what I wrote, and the Internet Archive can help you resurrect at least some of this material if you know how to look for it. But much of it no longer available online, due to link rot, revamped web sites, or, in the case of the AOL stuff, originally having been in a walled garden that no longer exists in any event.

For a long time I suspected that the stuff I wrote for the Fresno Bee would never be available online unless I put it there myself, but as it turns out, there’s a site, Newspapers.com, which will allow you to access at least scanned (and sometimes OCR’d) versions of my reviews and columns. I found out about this, weirdly enough, because some of my Fresno Bee movie reviews started being quoted at Rotten Tomatoes. Not the full reviews, just quotes, alas. I may get a subscription to this site just to download all my movie reviews at some point. That will be a project.

We have dug down far enough that now we come to the material that is, truly, not available in any way, shape or form online: Writing from high school and college, which includes but is not limited to, music reviews and columns for the Chicago Maroon, my college newspaper, and my first attempts at short stories from high school. The picture at the head of this essay is of the actual physical archive of much of this stuff. It does not include the big-ass book I have that compiles all the copies of the Chicago Maroon for the 1989-90 academic year, when I was the editor-in-chief of the paper; that’s on a shelf on the other side of the room. Yes, if there’s ever a fire in my office, all of this writing is likely to go up in smoke.

I may at some point scan some or all of this stuff, but I’m pretty confident that almost none of it, save for what I had already put up in the previous iteration of the site, is going to be seen by the public at large. Why? Well, one, at the ages of 14 to 21, I wasn’t that good of a writer. Indeed, there is a real and serious upgrade in my writing skills that happened in 1998, because between ’96 and ’98, I spent a lot of my time being an editor, and much of that time was telling other people how to tweak their writing to make it better. It meant when I looked at my own writing previous to that point, I was very much “who told this jackass he could write” about it. The word to use for my writing in high school in particular is “precocious,” which is to say, showing talent but not a lot of discipline or control.

Two, and again particularly in my high school writing, some of it I’m ashamed of. In more than one of my short stories from the high school era, I made being gay a punchline, not because I was virulently homophobic at the time, but because I was a kid and uncritically absorbed the general 1980s societal attitudes concerning gay and lesbian folks. That explanation doesn’t excuse it, and I’m not interested in pretending otherwise. Also, being an ignorant kid in the 80s would not mitigate actual pain and harm posting those stories would have on people here in 2026. So they will stay on their shelf and not online.

I’ll note that wisdom and empathy did not suddenly alight upon my shoulder upon high school graduation. There’s plenty of my writing in the 90s — when I was a full grown adult — that is absolutely cringe on reflection. I’d sorted most of my homophobia by my exit from college, but hashing out my tendency to fall back on casual sexism for a laugh took well into the 21st Century to deal with. I can and do still slip into what I might call “avuncular pontificating” mode, and especially in the early days of Whatever this mode was indistinguishable from generic mansplaining. I try to do better, and I’ve been trying to do better for a while now. We are all permanently works in progress.

But that does mean that, unlike when I was younger and thought everything of mine should be read, I now understand why people curate their work, and let lots of it slip out of view. There is work from every stage of my writing life I am proud of and happy to show people. There’s a lot more I’m fine with letting it be, or, at best, it being of interest to a biographer, should one be foolhardy enough to emerge. There is a reason why, in the Site Disclaimer for Whatever, I mention that when you come across something that sounds like me being an ass, check the date and see if there’s not a more recent piece that reflects my current position on the subject. Also, this is why, if someone presents me with something I wrote a a decade or two (or three!) ago, I am perfectly happy to say, when necessary, that younger me was a jackass on many things and this happens to be one of them.

While I’m on the topic, and this is a thing which I think these days is actually important given the current state of technology, this is why you can’t just feed everything I’ve ever written into a Large Language Model and have it shit out a reasonable facsimile of me. Leaving aside any other issue with the current model of “AI” being an unthinking statistical matching machine, I am a moving target. I am not the same writer at 56 that I was at 16, 26, 36 or even 46. Is there a consistent thread between those versions of me? Absolutely; you can read something I wrote as a teenager and see the writer I am now in those words. But the differences at every age add up. You can’t statistically average the circumstances and choices I made across 40 years into something that reads like me, either as I am today or how I was at any previous stage.

And yes, you could ask an “AI” to control for these things, and it will, but it’s still not going to do a great job. I am me because of the lifetime of experiences I have had, but that’s not all of what makes me who I am in any present moment, What in my experiences contribute to that are not all equally weighted, or of equal consideration when I write… or when I’m thinking about what to write next. An LLM won’t and can’t understand that, which is why an attempt to use one to write like me (or any other author) is an exercise in the Uncanny Valley all the way down. Recently someone tried to convince me an LLM could write like me by cutting and pasting to me something he had it write “in my style.” It was only vaguely like how I would write, and also, I was mildly concerned that this person thought this was actually how I wrote.

All of which is to say that there is a lot of writing from me, and mostly what it does is give you an insight into who I was at the time it was written. Some of it good! Some of it is not. Some of it you can find, and some you cannot. And while I very much want you all to buy every single novel in my backlist, Tor and I both thank you for your efforts on that score, otherwise I’m perfectly okay with you focusing on what I’m writing now rather than what I wrote way back when. I’m related to that guy, and we’re very close. But we’re not exactly the same person anymore.

— JS

LBCF: A GIRAT exclusive

Jan. 9th, 2026 10:09 pmA Quick Thought On Nice Moments With Strangers

Jan. 9th, 2026 10:03 pm 2026 has consisted of a few events that have contributed to my ever declining faith in humanity. I’m sure it’s done the same for many of you, so I thought today would be a good time to tell you about some positive interactions I had with strangers this past week, to remind us that not everyone is terrible, and we can still have nice moments in our personal life, even among strangers.

2026 has consisted of a few events that have contributed to my ever declining faith in humanity. I’m sure it’s done the same for many of you, so I thought today would be a good time to tell you about some positive interactions I had with strangers this past week, to remind us that not everyone is terrible, and we can still have nice moments in our personal life, even among strangers.

Yesterday, I drove to the next town over to get a coffee, and en route saw a man sitting on his front porch playing the banjo. On my return journey home I was stopped at the stoplight in front of his house, and I rolled down my window to listen to him. He was very talented, playing the banjo beautifully. He looked up at me and I gave him two thumbs up out my window and smiled at him. He smiled and returned to his skillful playing. The light turned green and I drove off.

A few days ago I was at Meijer, and a couple walked past me while I was looking at the bagels. The girl said “oh, bagels actually sound really good right now,” to which the guy replied, “you should grab some bagels.” She came up next to me and started looking at bagels, too.

“You should totally get bagels,” I reaffirmed.

“Well I saw you looking at them and thought they did sound good!”

“Did you see the cranberry ones? That’s what I grabbed, they sounded delish.”

“Ooh, those do sound good.”

“I’m about to go grab strawberry cream cheese to put on them.”

“Yum what a good combo!”

“Have a good one!”

“You too!”

I walked away, smiling.

So often I am completely indifferent to (or even resent) everyone else that’s at the grocery store, but sometimes it’s good to remember that the other people at the store are also just girls who want a bagel, like you. And normally I don’t strike up conversation, because who wants to be talked to while they’re grocery shopping, but something in me just sought connection with my fellow bagel shopper in that particular moment.

Just a couple days ago, a stranger came to my house to buy a microwave I had listed on Facebook Marketplace, and she said I had the most beautiful home on the block, and we had a brief conversation about moving troubles and how the house looked great. It made me smile. I’m glad she said something so nice, it really brightened my day.

Multiple times this week alone, strangers walking down the street or driving past me have waved, or nodded, or smiled, and it’s such a good recognition of, “hello, other human, I see you.”

Such small acts of acknowledgement that you exist and everyone else is a person like you. I don’t know, it just makes me feel better, and I thought maybe it would make you think of the last time a stranger smiled at you, too.

Feel free to share nice interactions in the comments, I’d love to hear them. And have a great day!

-AMS

A Monolith in Very Real Danger of Being Trampled By a Cat

Jan. 9th, 2026 03:24 pm

Here is Saja giving consideration to the upcoming trade paperback version of When the Moon Hits Your Eye, which will be out February 10, just in case you had nothing to do that day. It comes with an extra, namely an alternate first chapter of the book that I wrote but did not use, because the first chapter I did use fit my overall narrative better. But it is still good! And it has a cat!

Also, this quote on the back of the book:

Which makes me absurdly happy.

— JS

‘Is it right on red or left on MLK?’

Jan. 8th, 2026 09:35 pmThe Big Idea: Lance Rubin

Jan. 8th, 2026 07:41 pm

Many people wish they could return to a specific age in their life and live it all over again. But what if that person didn’t know they were reliving the same year over and over again? New York Times best-selling author Lance Rubin explores the idea of being a teenager seemingly indefinitely in his new novel 16 Forever. Follow along in his Big Idea to see a fresh take on the beloved time-loop trope.

LANCE RUBIN:

It’s no secret that we live in a culture that’s afraid of aging. Thousands of products exist to keep us looking as if we’re frozen in time. “Forever Young” is the name of not one, but two, classic songs. Forever 21 was a popular clothing store for decades.

But it occurred to me at some point that, if you could find a way to stay eternally young, it would actually be a complete nightmare. (Cue creepy, echo-saturated horror movie trailer version of Alphaville’s “Forever Young.”)

I said it occurred to me at some point, but I know exactly when it was.

I was five years old, watching a VHS tape of the 1960 televised Peter Pan musical starring Mary Martin. At the end, Peter comes back to the Darling home, and Wendy…has become an adult. They can’t hang out anymore. So instead, Peter flies off with Wendy’s daughter, Jane. Um, I thought, is this supposed to be a HAPPY ending? Seeing the playful bond between Peter and Wendy SHATTERED because of time? With Jane easily replacing Wendy simply because she’s YOUNG?

Around the same age, I saw the 1986 Disney film Flight of the Navigator, in which 12-year-old David falls in the woods and wakes up eight years in the future. His younger brother Jeff has become his older brother. Good god, it chilled me to the bone. The jarring role reversal. The visceral terror of time moving on without you.

And so, I decided to explore these ideas in a novel, with poor Carter Cohen stuck forever at age 16, literally unable to grow up. I’ve always loved a time-loop story, but the idea of a year-long loop, where every character knows the loop is happening except the person it’s happening to, rather than vice versa, seemed unique and intriguing.

I quickly realized that Carter’s perspective was an inherently disoriented one, seeing as his memory wipes clean every time he leaps back to the beginning of sixteen. It felt like the story wanted to be grounded in another POV too, to better understand the way Carter’s looping—which feels almost like a mysterious medical disorder—affects the people around him.

So the story is also told by Maggie Spear, the 17-year-old girl who Carter dated and fell in love with during his most recent loop. Once Maggie sees that the boy she loves now has no idea who she is, she decides it’s too painful to start over.

The experience of writing the first draft started pleasantly enough, as the premise gave me a lot to explore. It was fun to work through what a mess it would be to wake up thinking you were sixteen and then seeing your family had all aged six years without you. It was similarly compelling to think about the devastation of having your boyfriend walk right past you in the high school hallway because he has no idea who you are.

But when it came to cleaning up the mess these characters were in, I was pretty clueless.

As my editor David Linker said after reading my first draft, it “really falls apart in the second half.” The worst part about that note was that I knew he was completely correct.

I had two main struggles with this book. One was accounting for the six years of looping that happens before the novel even begins. Kind of an unwieldy amount of time to work with. I decided to write several chapters from the POV of Carter’s younger-now-older brother, Lincoln, since as a sibling he would have been there for every previous loop. That said, it was still hard to determine what had happened during that time and what was worth sharing with the reader.

The other struggle involved, well, THE LOOPING. Like, um, why was it happening? And would Carter get out of it? If so, how would he get out of it? How would that connect to the theme of growing up? Would a solution, if there was one, be clear or ambiguous? Literal or figurative?

Unlike a Groundhog Day loop of twenty-four hours, Carter had to make it through at least an entire year for the reader to see if he was going to make it out of the loop or not. Again, I’d boxed myself into a cumbersome duration of time. Which led to other questions too, like if Carter and Maggie were going to get back together, when in the year should that happen? How could I maintain the necessary tension when the ticking clock was A YEAR LONG?

So, yeah, imagine the above two paragraphs looping through my brain for months and months, as I paced around my apartment, as I walked to get groceries, as I talked through ideas with my wife Katie. I was, of course, as stuck as my protagonist—draft after draft after draft, unsure if I’d ever be able to write a version of this book I felt good about.

Ultimately, there were no quick solutions. No lightning bolt moment that solved everything. Instead, there were a series of tiny discoveries and changes that slowly made the book into something better. When my editor read the second draft, he felt it had improved, but it still fell apart in the last third. When he read the third draft, he felt like it was almost there, but not quite.

And so on and so on. There’s probably a reason writers are so attracted to the time-loop trope—in many ways, it so aptly represents the creative process: living something over and over and over again, trying to make it a little better each time.

Until finally: you stop looping. And it feels amazing, like you’ve done something impossible. I’m so happy with where the book finally landed and proud of the journey it took to get there. And, just as importantly: I have a deeper understanding of why Peter Pan and Flight of the Navigator made me feel so damn sad when I was five.

16 Forever: Amazon|Barnes & Noble|Bookshop|Powell’s|Libro.fm|Community Bookstore

Construction Time Again

Jan. 8th, 2026 03:46 pm

After a delay when the route from the manufacturer to us was literally closed by winter weather, all the components for Krissy’s new garage have arrived and the final construction has begun. One of the advantages of this type of construction is that it’s relatively quick to set up; the should have the whole thing up and insulated in a couple of days, after which time this garage will be the new home of our ride-on lawn mower and Krissy’s dad’s old pick up, which she has kept in meticulous shape and which still runs great.

Obviously I will post when the thing is completed, but I thought this early morning, snapped-when-I-took-the-dog-out shot was a pretty cool in-progress moment. I know Krissy will be happy when her new garage is done, and also, when all the construction mess is gone.

— JS